Recent inflation numbers from Nigeria are creating serious concern over the rising cost of food items in the country. But this is not Nigerians’ first encounter with food prices running hot, as the spikes date back roughly two decades.

Between January 2003 and August 2021, the food inflation rate has raced to three major peaks. The first and highest was about 38% in August 2005, more than 16 years ago.

The second, about 21%, was in July 2008. The third – the second-highest in 20 years – was about 23% in March 2021.

Many Nigerians believe that either the rising dollar or middlemen, or both, are to blame.

But there is another factor at the root of the problem: the average cost of transporting food from the comparatively more productive Northern states to least-producing Southern states within the country. Efficient transport infrastructure and local refining of fuel are key to solving the problem.

Crunching the numbers

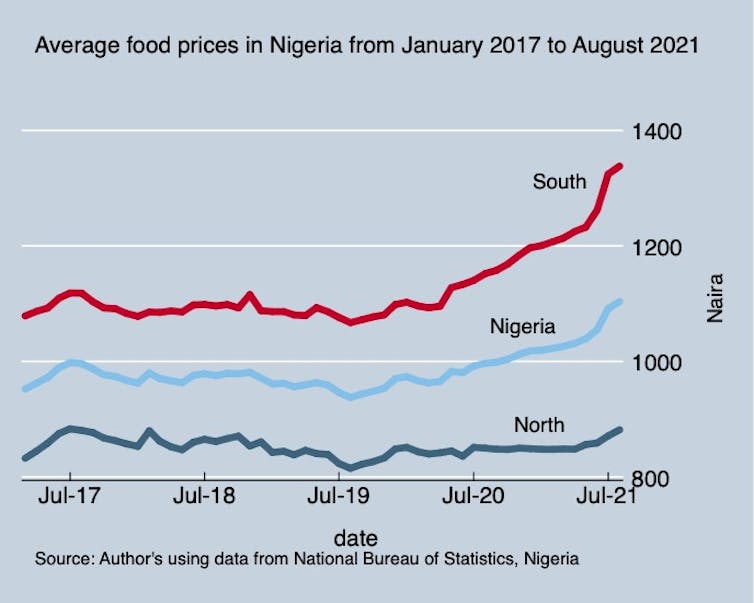

I obtained and used monthly data for the period from January 2017 to August 2021 from the National Bureau of Statistics.

The data relates to prices of 43 frequently consumed food items in Nigeria, including gari (cassava flour), rice, maize, beans, red oil, vegetable oil, meat, chicken, eggs, potatoes, yam and fish. It covers the 36 states in the country, including the federal capital.

I observed that all the states with the lowest food prices are in the north (Kano, Katsina, Gombe, Kebbi, Niger) and all the states with the highest food prices are in the south (Imo, Anambra, Rivers, Enugu, Bayelsa).

It’s clear that the north ‘feeds’ the south. But the north is not able to feed itself equally well. More than 25 million people (22% of the population) in the north are unable to spend roughly N200 (US$0.48) per day on food, compared to just 4 million (4% of the population) in the south.

I based my calculations on household-level welfare information collected by the national bureau of statistics between September 2018 and October 2019, and an annual food poverty line of N81,767 (US$198).

In doing so, I considered owned-food production, that is food not bought from the market but farmed and consumed by the poor. This is in order to account for food items farmers may cultivate directly for their consumption.

Farmers in the north are not benefiting (or seeing their incomes rise) as a result of rising food prices. Inflation is not transferring wealth from states that don’t produce food to states that do. Other factors such as the cost of imported petroleum products is mopping up the rise in prices.

Winners and losers

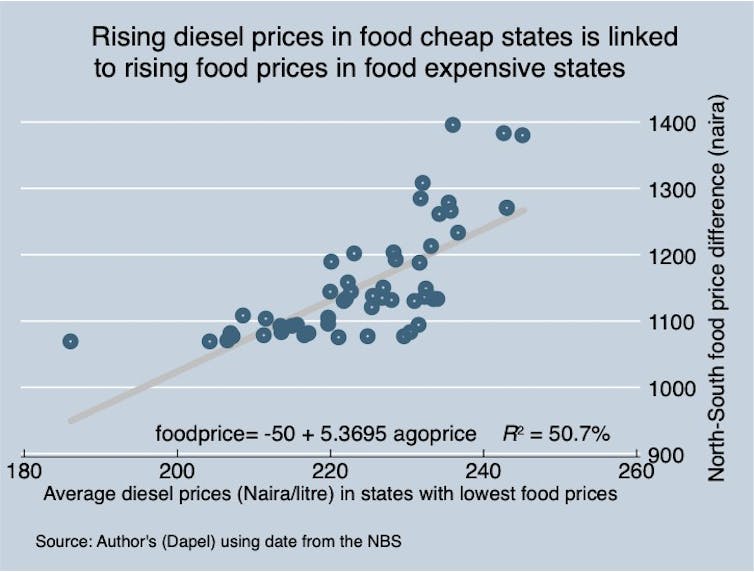

Rising average diesel prices in cheap-food states are linked to rising food prices in expensive-food states. Within the study period, diesel prices have risen by a national average of 67%.

Regionally, food items are usually transported on diesel-powered vehicles rather than petrol-powered vehicles. Since vehicles transporting food items from the north to the south will usually fill their fuel tanks in the north, it is plausible to compare diesel prices in the north with food prices in the south.

Author using data from the National Bureau of Statitstics, Nigeria

The recent sharp, steady spike in food prices started in August 2019. Nationally, between this period and August 2021, average food prices rose by roughly 18%, but lower in the north (8%) and highest in the south: 25%.

Apparently, the south is driving the rise in national food prices. It contributes 78% to the overall increase.

This fact, along with the diesel price connection, shows that the cost of transport is the culprit.

Author using data from the National Bureau of Statitstics, Nigeria

The chart above shows the relationship between the average fuel prices in five Nigerian states with the lowest food prices and the cost of food items in five Nigerian states with the highest average food prices.

It indicates a strong positive link between the two variables. For instance, an additional one Naira in the price of diesel in the north is expected to result in an additional five Naira in average food prices in the south.

Consumers of food items transported from the north to the south are paying a substantial part of the food inflation burden. They are the ‘losers’. But that doesn’t mean the northern farmers are winners.

Food prices in the south are higher than food prices in the north by an amount almost equivalent to the cost of transporting the food items from the north to the south.

Therefore, the likely winners may be living outside Nigeria: the oil marketers and those supplying refined petroleum products to Nigeria. About 80% of the country’s diesel is imported.

Rise of the dollar

Many Nigerians have the view that the depreciating value of their local currency is responsible for food inflation.

There is some truth in this claim. Based on a 2019 survey by the national bureau of statistics, 32% of Nigerian households reported buying imported rice. The price of imported rice will rise with the rising value of the dollar.

Based on my own calculations using data from the national bureau of statistics, I found that locally cultivated food items are responsible for 85% of the surge in food prices between August 2019 and September 2021. Imported food items are not driving up the food inflation rate, as foreign rice accounts for just about 2% of the food inflation.

The way forward

There are two ways to address food inflation in Nigeria. First, close the inter-regional price differences by setting up a more efficient transport system that connects the two major regions of the country.

One of the ongoing railroads projects in the country, linking Nigeria’s two commercial capitals – Lagos in the south and Kano in the north – is a welcome development.

Second, since Nigeria imports over 80% of its petroleum products, local pump prices must be divorced from changes in international oil prices if they are to be kept stable.

One way to do this is for the country to refine its fuel needs locally. This brings to fore the forthcoming Dangote refinery, which is expected to be the largest in the world. If it succeeds, it will play a key role in revamping Africa’s largest economy. It will raise Nigeria’s external reserves by replacing imports of refined petroleum products that cost about $7-$10 billion annually.

However, there are two vital questions that Dangote, the federal government of Nigeria and their deal makers must answer. First, the refinery is expected to pump and refine 650,000 barrels of crude oil per day. Will it pay for the oil in dollars? Otherwise, the refinery will cut Nigeria’s flow of foreign exchange by over $60 billion annually. This is based on my estimate using data on oil prices and oil production.

Second, how will the pump price be set? If the government steps back from its refining business and therefore stops setting the pump price as it is currently doing, Mr Dangote could possibly rule the Nigerian oil market.