Climate disasters are now costing the United States US$150 billion per year, and the economic harm is rising.

The real estate market has been disrupted as home insurance rates skyrocket along with rising wildfire and flood risks in the warming climate. Food prices have gone up with disruptions in agriculture. Health care costs have increased as heat takes a toll. Marginalized and already vulnerable communities that are least financially equipped to recover are being hit the hardest.

Despite this growing source of economic volatility, the Federal Reserve – the U.S. central bank that is charged with maintaining economic stability – is not considering the instability of climate change in its monetary policy.

Earlier this year, Fed Chair Jerome Powell declared unequivocally: “We are not, and we will not become, a climate policymaker.”

Powell’s rationale is that to maintain the Fed’s independence from politics and political cycles, it should use its tools narrowly to focus on its core mission of economic stability. That includes price stability, meaning keeping inflation low and maximizing employment. In Powell’s view, the Fed should stay away from social and environmental concerns that are not tightly linked to its statutory goals.

Win McNamee/Getty Images

However, it is getting increasingly difficult for central banks to ensure stability if they do not integrate climate instability into their monetary policies.

As researchers with expertise in climate justice and central banks, we recently published a paper reviewing the monetary policy tools available to central banks around the world that could help slow climate change and reduce climate vulnerabilities.

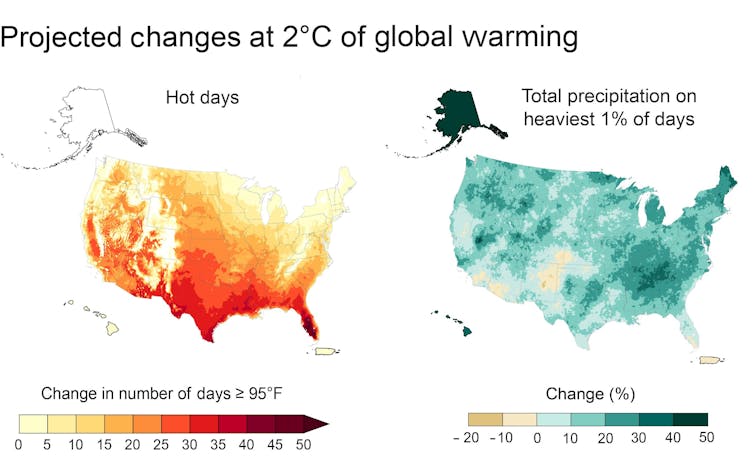

With the new U.S. National Climate Assessment and other research making clear that U.S. policies and actions are insufficient to minimize climate instability and manage the growing economic costs, we believe it’s time to reconsider the role of central banks in responding to the climate crisis.

Rethinking interest rates

One thing central banks could do is set lower interest rates for renewable energy development. The Bank of Japan has used this strategy.

The Fed’s aggressive increases in interest rates in response to rising inflation have slowed the transformation toward a more sustainable society by supporting fossil fuels and making investments in renewable energy infrastructure more expensive. Offshore wind power has been particularly hard hit, with multiple multibillion-dollar projects canceled as higher interest rates raised the projects’ costs.

AP Photo/Charles Krupa

One way to introduce differentiated rates would be to create a special lending facility under which commercial banks could borrow money from the central bank at preferential interest rates if used for renewable energy deployment or other climate-friendly investments. Whether the Fed already has authorization to do that depends on interpretation of its current mandate.

While the U.S. Federal Reserve has not done it before, China’s central bank has used similar tools to incentivize renewable energy, and the Bank of Japan’s lending facility offers zero-interest loans for green investments.

Nudging banks to rethink investments

Despite the Fed’s proclaimed efforts not to pick winners and losers, its monetary policies have taken steps that favor established industries and companies, including the fossil fuel industry.

For example, the Fed supported the financial sector unconditionally during the COVID-19 pandemic to keep credit available to limit economic harm. Its massive purchases of corporate bonds resulted in subsidies to the fossil fuel sector.

Our analysis suggests two ways to help manage climate change now: The Fed can reinterpret its current statutory duties and start viewing climate action as a critical part of its role in maintaining economic stability within its existing mandate, as the European Central Bank has done, or the mandate of the Fed can be changed by Congress to explicitly include “green” transformation objectives, similar to the U.K.’s mandate for the Bank of England.

Either of these options could empower the Fed to address climate change and support the government, businesses, banks, households and communities in financing climate mitigation and adaptation efforts.

Fifth National Climate Assessment

The Fed could also discourage banks and investors from investing in assets that ultimately harm the economy – for instance, by setting collateral requirements for banks that would reduce the attractiveness of holding carbon-intensive assets. The European Central Bank recently announced that it would tilt purchases of corporate bonds toward “green” assets.

The Fed has recently taken steps to push large financial institutions to monitor climate-related risks in their portfolios, drawing the ire of Republicans, who claimed the bank had no authority to consider climate change. Whether this risk management approach will pressure banks to change their lending patterns is not yet clear.

The Fed and other central banks could go further and mandate energy transition planning with an eye toward economic stability. The European Union developed a whole new sustainable finance framework designed to discourage investment in economic activities that do not support an energy transition along the lines of the European Green Deal, which aims to turn Europe into a climate-neutral continent with no one left behind. The European Central Bank is obligated to support EU economic policies, including the green transition.

The Fed has used creative tools before

Many times in its 110-year history, the Fed has provided financial support to the U.S. government during major crises, such as wars and recessions, by offering direct lines of credit or by directly purchasing Treasury bonds. During the pandemic, it took extraordinary steps to keep U.S. businesses running.

Now that the U.S. is facing rising costs from the climate crisis, we believe the Fed should treat climate change with the same urgency and importance.

Kylie Cooper/Getty Images

In our analysis of the tools available to central banks, we took a climate justice perspective, looking beyond greenhouse gas emission reductions to incorporate social justice and economic equity. Instead of focusing on supporting corporate interests and the financial sector in the short term to stabilize markets, we believe central banks could prioritize longer-term stability by funneling investments toward vulnerable communities and people.

The Bank of England, the European Central Bank and other central banks are already implementing some pro-climate measures. At the Fed, Powell seems more concerned with political backlash than the economic damage to the U.S. economy outlined in the latest climate assessment.

We believe it is past time that the Fed consider climate destabilization as a major economic crisis and use more of the tools in the central bank toolbox to tackle it.